“I like what you said, but I’m not changing anything that I’m doing.”

This sort of feedback should sound familiar to many educators. It’s what Cory Concus, a math teacher at 2015 SCORE Prize finalist Covington High School, initially heard from a fellow faculty member last year.

At the time, Mr. Concus had just taken on an instructional coaching role at Covington, spending mornings in the classroom and afternoons working with colleagues to improve instruction. Thanks to Covington’s instructional coaching and collaborative process, the attitude changed quickly.

At the time, Mr. Concus had just taken on an instructional coaching role at Covington, spending mornings in the classroom and afternoons working with colleagues to improve instruction. Thanks to Covington’s instructional coaching and collaborative process, the attitude changed quickly.

Two weeks later, the reluctant colleague asked Mr. Concus for more information, then tried something new in his classroom – he spread a sheet of butcher paper across a corkboard and let kids plot out how they all solved math problems. Students found multiple methods and stepped in to help one another find faster paths. It became clear to the teacher that something powerful was happening: Students were learning how to think about the skill being taught, and how to articulate their processes.

“He came and said, ‘You wouldn’t believe what happened in my class today,’” Mr. Concus recalls.

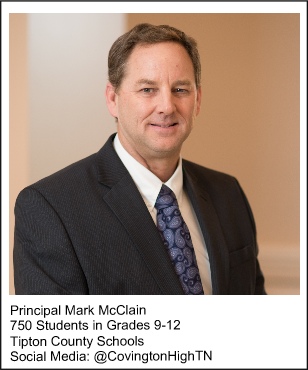

At Covington High, which serves nearly 750 students in grades 9-12 in West Tennessee, a collaborative, teacher-focused atmosphere ensures that instructors are respected, treated as experts in their field, and encouraged to work together closely. The resulting culture is highly conducive to innovation, instructional risk-taking, and development of leadership.

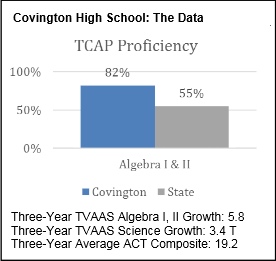

Covington students, in turn, benefit academically and personally. The school has narrowed achievement gaps while raising algebra proficiency rates. Covington’s students have made strong gains in English II and tremendous gains in Algebra I and II over the past three years. Covington was the SCORE Prize high school winner in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

“We treat our faculty as the professionals they are,” said Principal Mark McClain. “Once teachers enter our building, they feel that sense of family.”

The school has high levels of attrition and very little turnover. When Mr. McClain became a Covington teacher in 2005, he was one of 17 new faculty members. Last year, however, there was just one. Teachers tend to stay for extended careers at Covington.

“We have more people wanting to get in the door than wanting to get out the door,” said Brandi Blackley, assistant principal at Covington.

Covington offers outstanding leadership opportunities for teachers, allowing staff to grow while remaining at the school. Ms. Blackley was initially hired as an English teacher at Covington, then took on an instructional coaching role that allowed her to continue some classroom work while helping colleagues and serving as a part-time administrator. Now in her first year as a Covington assistant principal, Ms. Blackley is well positioned to join a building leadership team that meaningfully supports instruction.

“It’s about trust with your faculty, understanding that they are the content experts. As administrators, you have to trust them to teach the classrooms,” Ms. Blackley said. “We expect that you know your content and that you know your kids. If you know your content and you know your kids, things typically fall into place.”

Trust and respect for faculty shines through the school’s instructional coaching and professional learning communities (PLC) structure, two defining features of Covington’s culture. In place for the last five to seven years, PLCs are led by teachers and instructional coaches. Meetings are every two weeks, alternating between grade-level and departmental groups.

Mr. Concus believes that a structure based on teachers leading and coaching other teachers keeps the process highly focused on instructional needs and student improvement. As an instructional coach, Mr. Concus doesn’t dictate changes; he shares his own daily struggles and successes. And because he is still teaching, he remains well-connected to students, which translates to connections with other teachers.

Support for teachers also comes from outside the building. The central office of Tipton County Schools is an essential part of Covington’s achievements, Mr. McClain says, as are members of the local community and nearby industries.

Support for teachers also comes from outside the building. The central office of Tipton County Schools is an essential part of Covington’s achievements, Mr. McClain says, as are members of the local community and nearby industries.

“We’re only as successful as the support we have,” Mr. McClain said.

Covington teachers face many challenges posed by the school’s demographics. Poverty levels are high. In a community that has experienced dramatic economic changes in recent years, a large number of students deal with significant challenges before they enter the school building each day. The school’s staff understands this, and embraces it. More than half of Covington’s teachers are also alumni of the school. Many of the rest are parents of school students and alumni. Mr. Concus is part of the latter group, with a 17-year-old daughter currently attending the school.

“This is hard work, but just look at the change that’s taking place in some of these kids. If one kid turns it around, that can change a whole generation of students,” said Mr. Concus. “We’re just kind of a blue-collar family. We really have a hard and tough task ahead of us. If you walk through the hallways, you recognize very quickly that demographics are not always conducive to learning. But it’s our job to make sure every kid learns.”

This gets to a hallmark of Covington life: Pride. Students and teachers are happy to be there, Ms. Blackley said. And kids who are part of the school automatically have an extended network of support in the local community.

“We do so much more than just make sure everyone has a diploma,” said Ms. Blackley. “There’s a lot of pride. Teachers accept zero excuses. That comes from what they expect of themselves.”