One afternoon in May, I rushed out of my middle school to interview for a summer fellow position at SCORE. Even though I had found someone to cover my after-school bus duty responsibilities, I was still running late because I was stopped by a student, then a parent, and then my principal.

For any teacher in Tennessee who’s tried to make a doctor, bank, or car appointment during the school day, you probably understand the struggle. I was convinced that my tardiness would leave me without a summer job, a job that I needed so that I could afford my year-round one.

Prior to my interview, I was asked to write a synthesis on education reform in Tennessee–and to keep it under 500 words. As I started to write and reflect on my five years in the classroom, this seemed like an impossible task.

In 2012, I remember teaching two sets of standards, after reform pushed higher expectations for our students. By 2013, I felt comfortable explaining the district’s grading policy to new teachers and in 2014, I finally understood how I was evaluated using the TEAM rubric.

In 2015, I felt excited about new restorative justice practices and in 2016 was thankful for my school’s efforts to implement social and emotional health initiatives–which translated to starting every day in advisory. However, I will admit that reform felt like it was happening to me, as opposed to with me. I will also admit that as new initiatives on everything from assessments to zero tolerance policies flooded my inbox, I operated in survival mode with the fixed mindset to just close my door and teach.

While I’ve done my best to be aware of changes in policy in order to best advocate for my students, the SCORE fellowship provided a structured time and space to be fully immersed and undistracted in policy work . I’ve learned, during my two months at SCORE and in my efforts to implement health programming at my school, that my fixed mindset was not what’s best for me and was not what’s best for students. I’ve learned less about specific reforms and more about why change was vital, from a negative report on Tennessee education outcomes from the US Chamber of Commerce in 2007 and students’ gaps in opportunities and health that still exist today.

In 2015, after noting student health misconceptions, I worked with my community to implement a health program to increase access health education to over 100 female students. To design a program that would be both relevant and engaging for my students, I met with parents and students, reviewed district and state policies on health programming, and incorporated feedback from students.

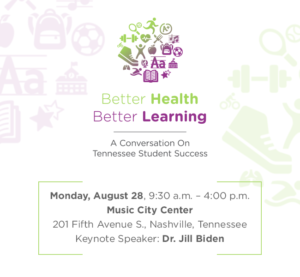

I have continued this work at SCORE, where I have supported planning for the Better Health, Better Learning Summit. At the summit, national health and education experts will convene in Nashville to deepen their understanding of research, highlight gaps in student outcomes and access to student services, expand awareness of innovative practices, and foster collaboration. As a teacher, I hope this work highlights the importance of student health and is the start of many innovative partnerships, programs, and policies to better serve the need of our students.

As I conclude my time at SCORE to start my sixth year in the classroom I am already anxious about the new set of science standards that won’t even be implemented until 2018. However, I feel confident knowing I will enter the classroom with a new understanding of policy and the people who shape it to better serve my colleagues, my parents, and my students. More importantly, I will enter the school year with a new openness to the word “reform,” as it’s up to me to make sure I don’t close the door.

Interested in attending the Better Health, Better Learning summit that Madeline worked on over the summer? See the agenda for the August 28 event and then register.